Alex explains how to use back pressure with your OpenFaaS functions to make sure all your data gets processed.

As I’ve spoken to customers and community users of OpenFaaS, I’ve noticed a common theme. Users want to process large amounts of data through a number of functions and get results out the other end.

The goal is to process a dataset as quickly as possible, without losing any of the records.

I’ve seen friction in these areas:

- timeouts being met on the gateway, queue-worker, or function

- errors manifesting in functions that were not present under light load testing

- dropped messages due to over saturating a function vs. how many requests it can process concurrently

- understanding patterns for retrying and coping with limits set in functions

- knowing how and where to look for specific type of errors

I’ll set out to explain why setting limits is important in a distributed system, along with a pattern called “back pressure” which can be used to ensure all of your requests get processed without losing data.

Why do we want limits?

I started creating OpenFaaS in 2016 for three primary reasons: I wanted to run code in any language or runtime, be able to deploy it on any server or cloud, and to be able to set my own limits for timeouts, function size, and event sources for integrations.

OpenFaaS gives you the flexibility to pick and choose a timeout that makes sense for your workload, instead of being fixed at 60 seconds. For asynchronous requests, there’s a default limit for the payload size, however you can also change that.

So if we can pick our limit, why even have one?

Limits are important for understanding how a system will behave and how it can break, and even when we don’t set limit explicitly, there may be some implicit ones which we are not aware of.

Let’s say that you configured a function to a limit of 1GB of RAM available for processing requests. You then load it with 1,000,000 requests. It’s likely that it will break in correlation to the ulimit which is set up on the host. The ulimit values control how many processes can be started and how many files can be opened.

A request to an OpenFaaS function uses at least one file descriptor up, which means if we have a descriptor limit of 1024, we will be able to handle somewhere between 1 and 1024 connections concurrently. We then need to bear in mind the RAM limit that has been set, and which we may encounter first.

ulimits can be configured, so let’s assume that the RAM and amount of connections is high enough for our load.

When a function runs out of file descriptors for new requests you may see errors like “Connection cancelled” and eventually, “connection refused” followed by a pod restarting. When a Pod runs out of memory, and reaches its limit, it will simply be terminated by Kubernetes.

If we have enough connections and RAM, then what else could go wrong?

Any external resources that your function makes use of may also have their own limits, such as the number of database connections opened. Connection pools can help here to some extent, however they also need to be configured and could run out of capacity. If, practically we can only open 10 connections to a Redis server, can our function handle more than 10 concurrent requests?

What if we have a downstream legacy API? Simon Emms implemented OpenFaaS at HM Planning Inspectorate and told me that he had to implement a retry and backoff process in his functions because the downstream API they used was legacy, couldn’t be changed and would fail intermittently.

What’s back pressure?

When applied to computer science, back pressure says that at some point we may have saturated the system or the network.

There are three strategies we could apply:

- Stop producing or slow the producing of load on the system

- Cache, save, or buffer requests

- Drop, delete or refuse new requests

OpenFaaS functions can be invoked synchronously or asynchronously over HTTP, or via an event broker like Apache Kafka or AWS SQS. It may be impractical for us to stop events being published to an Apache Kafka topic, but we could potentially stop consuming the events and let them buffer in the event log. When HTTP requests come from the outside world to a publicly accessible endpoint, that is going to be challenging.

One pattern we may want to consider is rate-limiting, which you will encounter if you start writing an application against a popular REST API like Twitter or GitHub. The HTTP code you will receive could be: “429 Too Many Requests” along with an optional header with an estimated time in the future when you should retry the work. This puts the onus on the producer to cache, buffer, or drop requests.

The OpenFaaS Asynchronous system implements a buffer whereby any request that is made via an asynchronous URL is published to a NATS queue. This is a form of buffering, and can shield a system from spikes in traffic. NATS Streaming has a default limit of 1,000,000 messages and around 1 GB of disk space, these values can be set higher if required. We need to bear in mind that the NATS queue is not infinite, and what could happen if it was saturated.

Finally, dropping of messages could happen at any component of the system: the gateway, the queue, the function, or an API that the function calls. When the Twitter API returns an error due to a rate-limit, this is a form of “dropping”.

When working with a team at Netflix who were exploring OpenFaaS for video encoding, they brought up a good point about limits. They were able to set a memory limit of say 128MB and then invoke a function which ran ffmpeg (a video encoder), and cause it to crash.

The solution was to set a hard limit on the number of concurrent requests for the OpenFaaS watchdog. Then, if the limit was set to “1”, any subsequent requests would be dropped with a 429 error. This assumes, that just like the Twitter API, the producer is ready to buffer the request and to retry later on.

Implementing back pressure and retries in OpenFaaS

In OpenFaaS Pro, we tied all of these concepts together.

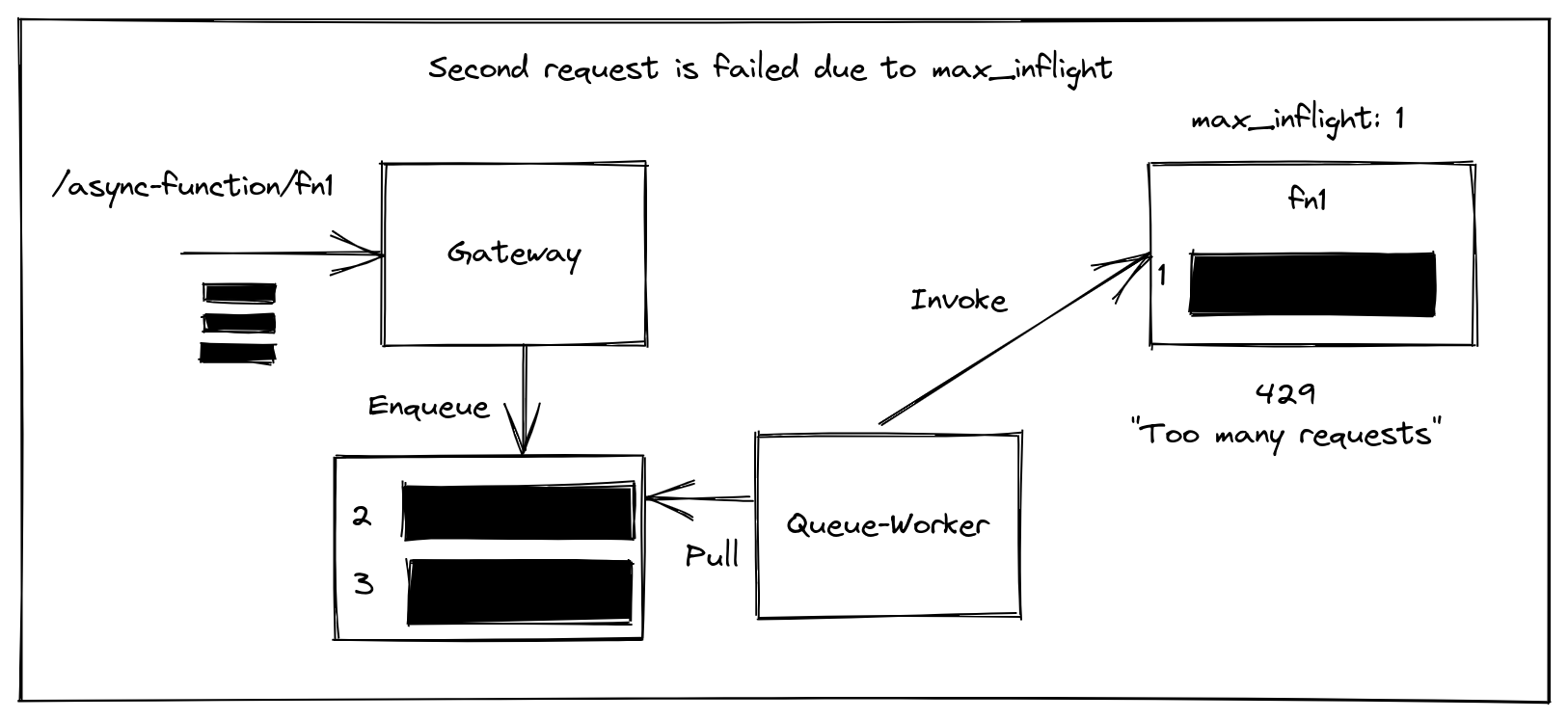

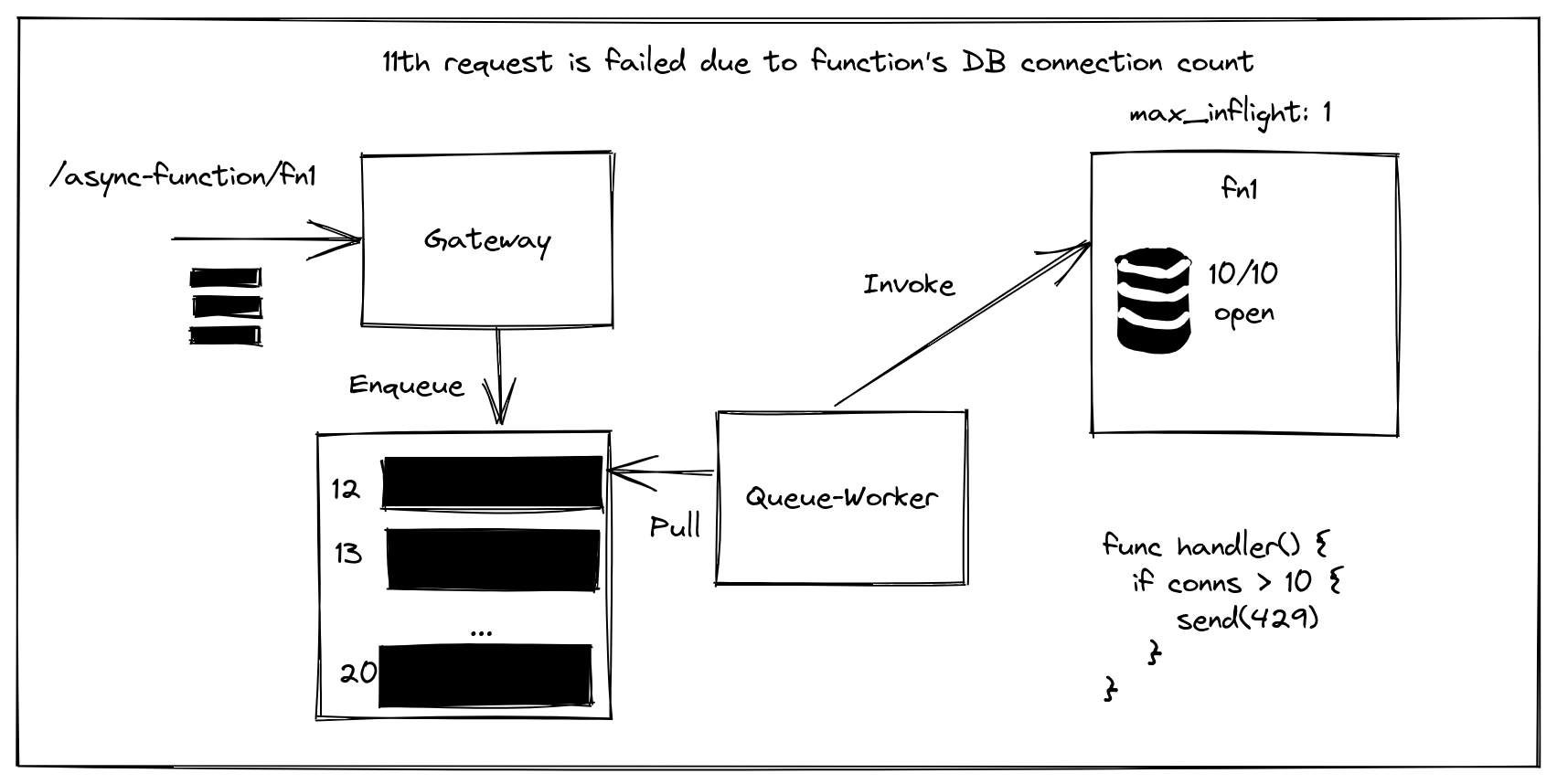

The second request receives a 429 message

Three messages are enqueued.

- The first is dequeued by the queue-worker which invokes the function and it starts executing.

- The second request is dequeued, but unfortunately, the

max_inflightvariable is set to 1, and the first request is still executing. - The function returns a 429 status code, and the queue worker rather than dropping the message simply submits it back to the queue. The delay is calculated to increase exponentially.

When the first message completes, the second message can be processed and so forth.

The OpenFaaS watchdog has a built-in environment variable called max_inflight which can be set to enforce the maximum amount of inflight requests or connections.

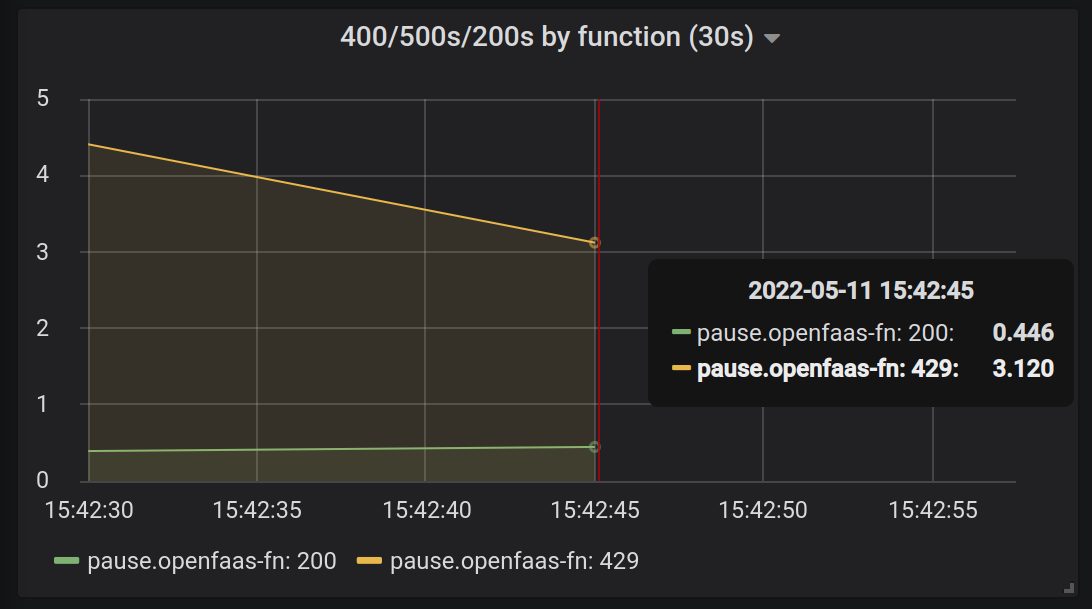

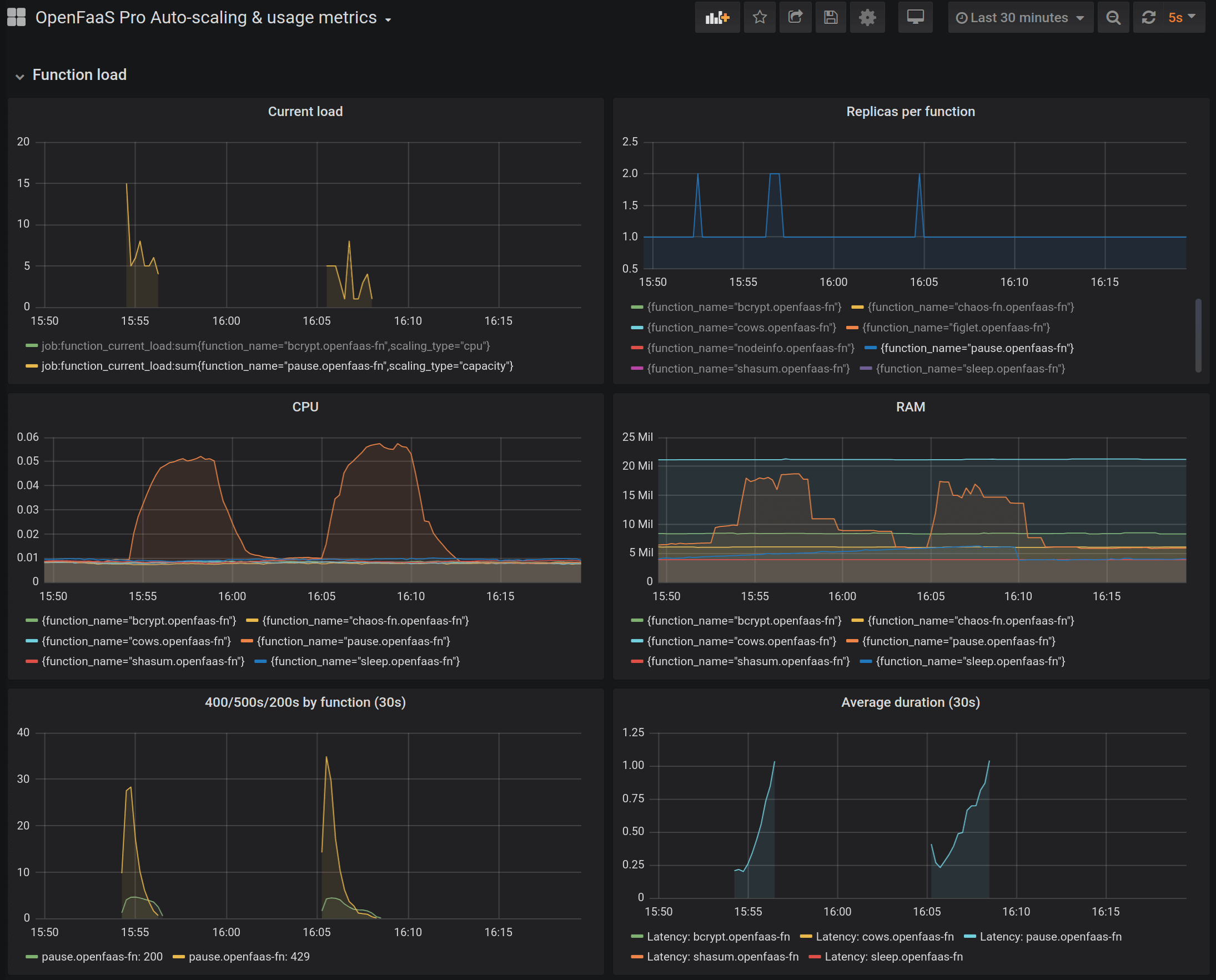

You can view the 429 errors by looking at the metrics in the OpenFaaS Pro Grafana dashboard or the PromQL query:

rate(gateway_function_invocation_total{code=~"4..|5.."}[30s] ) > 0

Deploy a function to pause for 1 second, it will simulate our ffmpeg video transcoder:

faas-cli store deploy sleep \

--name pause \

--env max_inflight=5 \

--env sleep_duration=1s

Then queue up 30 asynchronous requests.

hey \

-n 30 \

-c 1 \

-m POST \

-d "" http://192.168.1.19:31112/async-function/pause

A number of 429 responses were received from the watchdog

A number of 429 responses can be observed which are returned from the watchdog and retried by the queue-worker. Why do we see the 429 response? Because we set a limit for the function to process 1 request at a time at maximum, but had 30 requests queued up and ready. Importantly, note that we have no 500 errors - no data is lost, and you can count the number of 200 responses to see that they were all processed.

The new OpenFaaS autoscaler can be configured to scale functions based upon the amount of concurrent connections, which makes it a good pairing for this use-case.

We can use additional labels to set up the autoscaler in capacity mode. It then knows from the target label to create enough pods to handle roughly 4 requests per pod.

faas-cli store deploy sleep \

--name pause \

--env max_inflight=5 \

--env sleep_duration=1s \

--label com.openfaas.scale.target=4 \

--label com.openfaas.scale.type=capacity

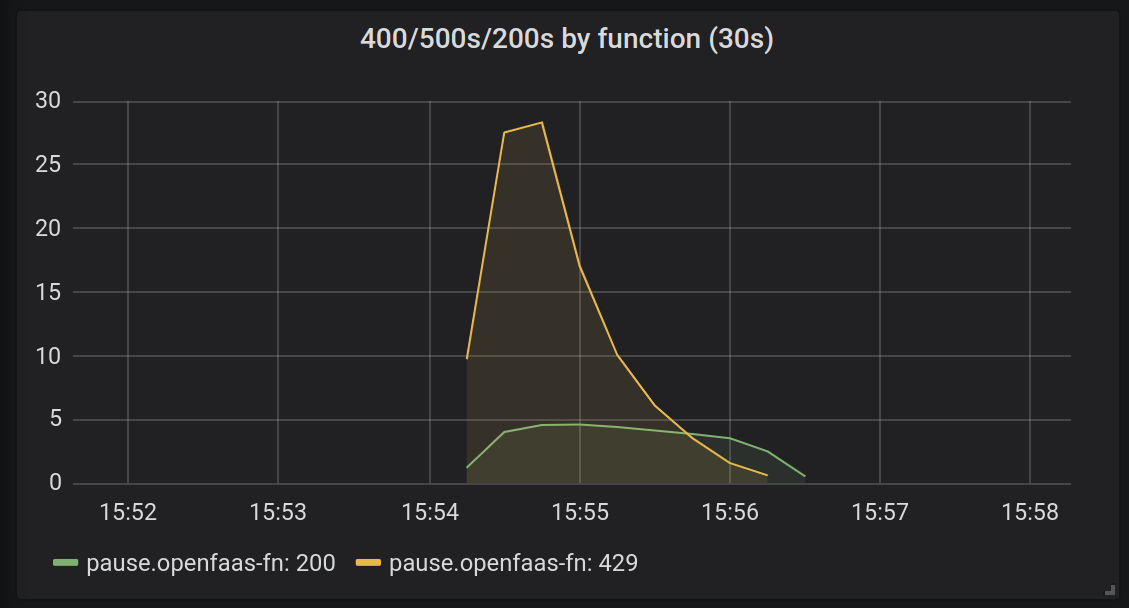

Now, given enough load - let’s say, 500 requests instead of 30, we should see the autoscaler kick in and add more pods, so that we have fewer 429 messages being produced, and more messages being handled by available replicas.

Many more requests come in at once, and are retried, but as the system scales, the retries drop off.

Coming back to limits, we will also need to consider the minimum and maximum amount of replicas we want for the function using the com.openfaas.scale.min and com.openfaas.scale.max labels:

faas-cli store deploy sleep \

--name pause \

--env max_inflight=5 \

--env sleep_duration=1s \

--label com.openfaas.scale.target=4 \

--label com.openfaas.scale.type=capacity \

--label com.openfaas.scale.min=1 \

--label com.openfaas.scale.max=20

Just like we define limits elsewhere, there is also a limit for the amount of times we will retry a message before dropping it. You can set this to a very high number if you wish. See details in the links at the end of the article.

In addition to limiting the number of inflight requests using the mechanism contributed by Netflix, you can also use your function’s handler to reject a request.

The function can fail a request

In the diagram, we may have our function fail a request when we meet our contrived connection pool limit of 10/10 connections.

We may also want to drop requests when we are nearly running out of disk space, especially if data or other files being fetched from S3 for processing.

A couple of weeks ago I spoke to a user who wanted to reject requests when the function was getting close to its memory limit.

Conclusion

OpenFaaS was built to avoid vendor lock-in, so it could run on other clouds and on-premises with very little change required to the setup. It also gives us the freedom to pick limits for things that are usually hard-coded in a SaaS or Cloud Functions product like the timeout for a function, or how many concurrent requests it can receive.

Ultimately, we still need to understand the limits and how they can work together, but we can tune them, and together with a back-pressure pattern, can ensure we do not lose data when the system becomes saturated.

OpenFaaS emits a number of metrics to help you understand errors due to saturation:

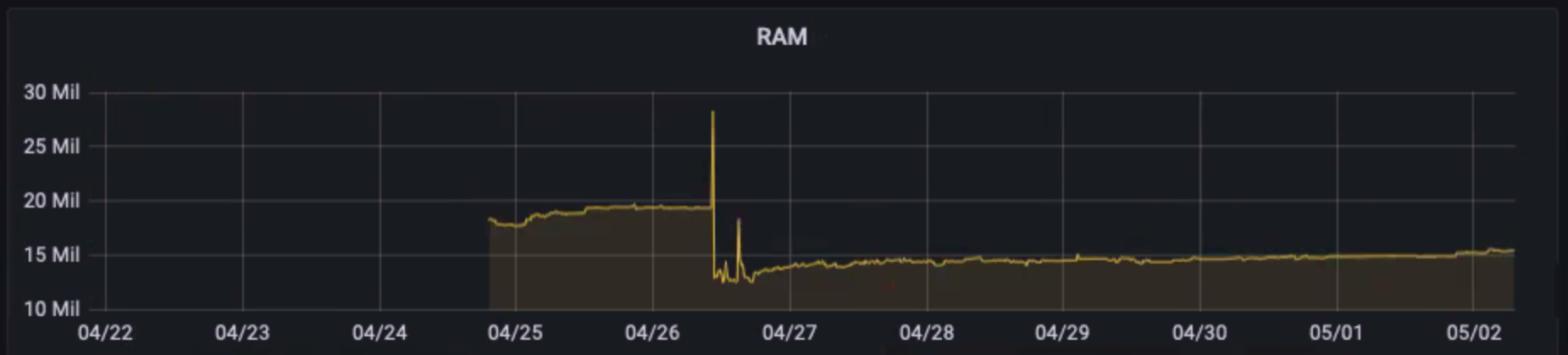

Billy Forester of Check Point Software recently told us about a memory leak he found and fixed by monitoring his functions during a spike in customer traffic.

The diagram below has been shared with his permission.

Detecting a memory leak in one of Billy’s functions

The fix? Remember to call defer r.Body.Close() in those HTTP handlers!

For OpenFaaS Pro customers: Download our recommended Grafana dashboard

Find out:

- How to configure Expanded timeouts for OpenFaaS

- How to implement back-pressure with retries

- How to make use of asynchronous invocations

- How to configure autoscaling

You may also like: