Learn what changes we made to help a customer scale to 15000 functions and beyond.

Introduction

In this post I’ll give an overview of what we learned spending a week investigating a customer issue with scaling beyond 3500 functions. Whilst navigating this issue, we also implemented several optimisations and built new tooling for testing Kubernetes at scale.

If you’ve ever written software, which other people install and support, then you’ll know how difficult and time-consuming it can be to debug and diagnose problems remotely. In this case it was no different, with our team spending over a week of R&D trying to reproduce the problem, pin-point the cause, and remediate it.

We had a support request from a customer that was running more functions than the typical team, so we decided to take a look at the problem and see what we could do to help them out.

In this post, you’ll see my thought process, and input from the OpenFaaS and Kubernetes community. Thanks to everyone who made suggestions or the problem over with me.

How many functions is a normal amount?

You may be tempted think of “serverless” through the lens of a cloud hosting company like AWS, Google Cloud or Azure, and their large scale multi-tenant products. With that perspective, it’s tempting to think that every other functions platform should work in exactly the same way, and at the same scale, going up to millions of functions per installation.

We should perhaps pause and understand the target user for OpenFaaS, which is largely self-selecting and made up of individual product teams.

We are aware of a handful of users running thousands of functions in production, usually as part of a system to provide customers with a sandbox for custom code. More recently, we’ve started to work with ISPs around the world who want to bring a functions experience to their platform, but even there, uptake takes time, and may never quite hit the numbers of a large cloud company.

Most users adopt OpenFaaS for portability, to be able to install on different clouds or directly onto customer hardware, for cost optimisation vs hosted functions, or in the case of Surge, because the of all the effort that’s been spent on the developer experience. You can build, test and debug functions on your laptop with the same experience as you’d get in production.

“OpenFaaS has been insanely productive for our business. The ability to run the whole stack locally is really important for our developers, and the async system based upon NATS JetStream means we can fire off our jobs and forget about them. We’re now turning to Kubernetes deployments and converting them into functions.”

So it’s not that we discourage large scale, or function hosting, we are seeing growing customer interest there, it’s just that OpenFaaS is popular with individual project teams who have a few dozen functions.

What does it cost to test at scale?

In addition, with OpenFaaS running on top of Kubernetes, we have to provision a whole node for every 100-110 containers that are provisioned, including control-plane, service mesh and networking. So for 3000 functions, you need at least 30 nodes.

We all know that clusters are slow to create on a platform like AWS Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS), and then adding nodes can take a good 3-5 minutes each. I did a calculation with the AWS cost estimator and to get to 3500 functions, you’d probably be looking at a spend of 1500 USD / mo in infrastructure costs alone.

How did we find the problem?

The problem was finally found after spending over a week building optimizations, and it was frustratingly obvious.

Building the test rig

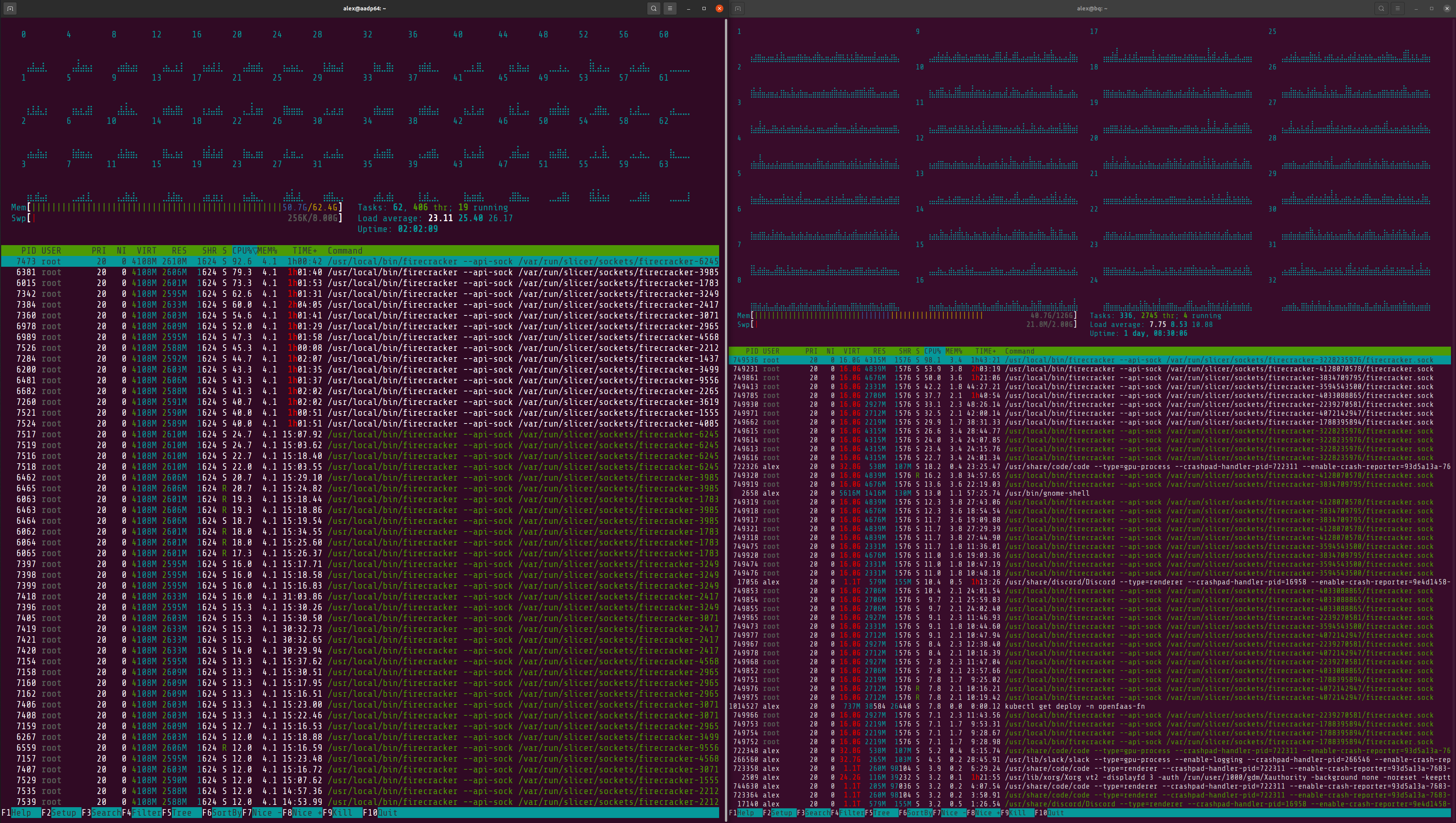

I started off by looking to hardware that I already owned. My workstation runs Linux and has an AMD Ryzen 9 5950x with 16C/32T with 128GB of RAM. Then, behind me sits the Ampere Developer Platform with 64C and 64 RAM. I paid an additional 500 USD to upgrade the Ampere machine to 128GB RAM in order to recreate the customer issue.

The container limit of 110 per Kubernetes node means that even if you have a bare-metal machine like this, it’s largely wasted, unless you are running a few very large Pods.

Could existing testing solutions help?

A friend mentioned the community project Kubernetes WithOut Kubelet (KWOK) as a potential option.

I did some initial testing here, and showed my work, for numerous reasons, it did not work for this use-case.

You can read the thread here, if interested: Testing an Operator with KWOK.

Could we slice up the bare-metal?

So what to do? My first instinct was to use multipass, a tool that we’ve been using for faasd development and for testing K3s, to create 30 VMs on each machine, combining them to get a 60 node cluster, which would allow for going up to at least 6000 functions, 2x over where the customer’s cluster was stalling.

the Ampere Dev Platform by ADLINK was used for initial testing

Multipass created 10 nodes in about 15 minutes, then when I the command to list VMs, it took about 60s to return the results. I knew that this was not a direction I wanted to go in.

Having written actuated over a year ago, to launch Firecracker VMs for GitLab CI and GitHub Actions jobs, I knew that I could get a workable platform together in 2 days to convert the bare-metal machines into dozens of VMs. So that’s what I did.

From the outside, it looked like the code had locked up or got stuck. After reproducing the issue, I decided to add a Prometheus histogram metric to see how often the reconciliation code was being called, and to see how long it took for each call.

The duration of the function was less than 0ms, so it wasn’t hanging. Then I noticed that the count of invocations was increasing at 10 Queries Per Second (QPS).

It turned out that the samples provided by the Kubernetes community use an internal rate-limiter with a value of 10 QPS, it sounds so obvious when you find it, but it took a week to get there.

I left the tests running overnight and saw for 65000 functions, which had not changed, the function had been called 1.1M times. This again was due to a faulty piece of code inherited from the original community sample called “sample-controller”. I spoke to Dims who works on Kubernetes full-time and he sent a PR to resolve the issue so it won’t affect others who are following the sample to build their own controllers.

After my initial testing of 4000 functions on a cluster built with my slicer tool across my workstation and the Ampere Dev Platform, I wanted to go large, and show that we’d fixed the issue. I set up 3x servers on Equinix Metal with an AMD EPYC with 32C/64T and 256GB of RAM.

My configuration was for 5x servers using 16GB of RAM and 8vCPU each, and then the rest of that machine, and the other three were split up into ~ 30 nodes of 2x vCPU and 8GB of RAM.

Put some K3sup (ketchup) on it

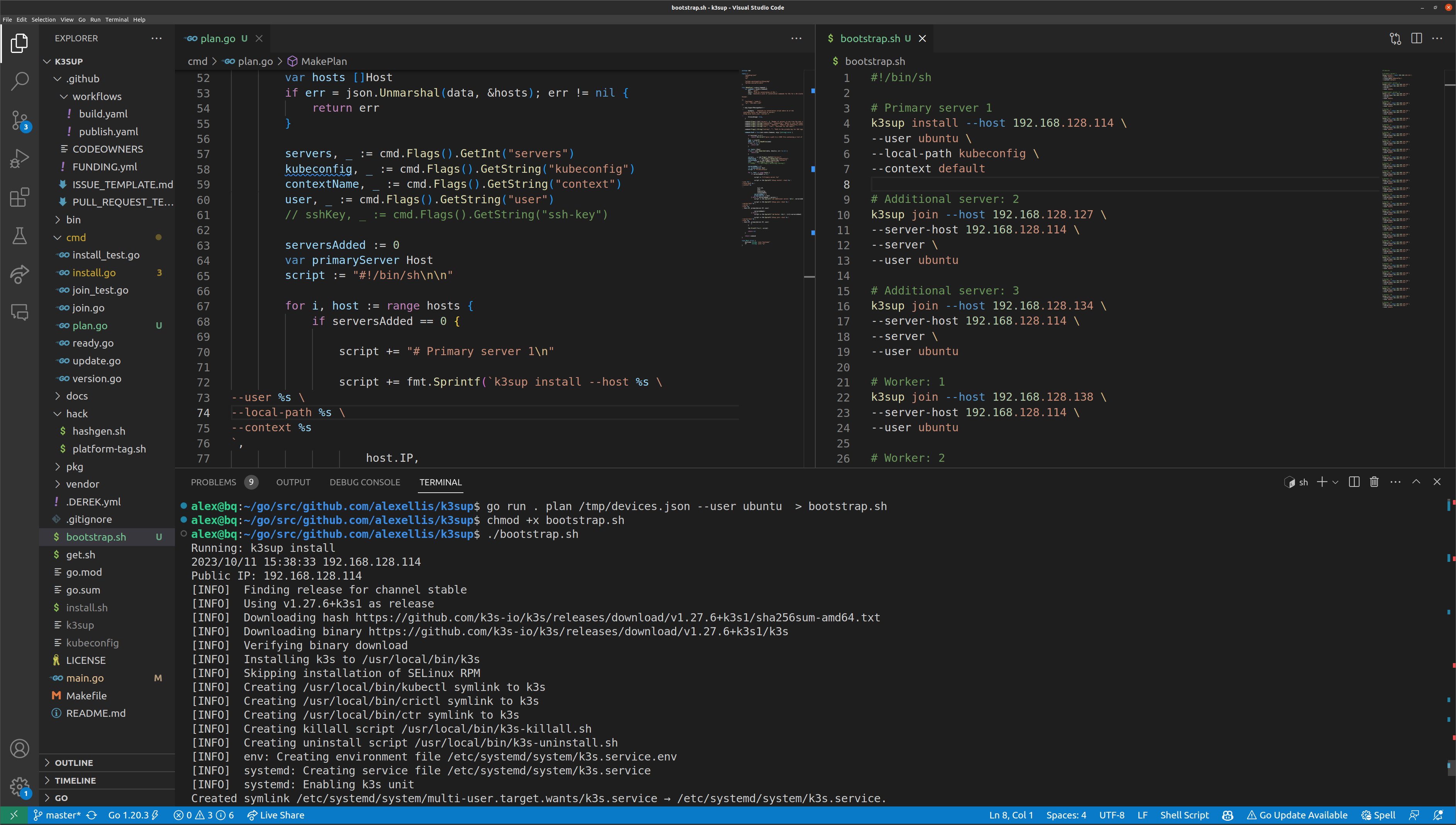

As the author and maintainer of K3sup, I knew that K3s would be a really quick way to build out a High Availability (HA) Kubernetes cluster with multiple servers and agents. K3sup is a CLI command with an install and join command which are expected to be used against a single host at a time. There needed to be a way to make this more practical for 60-120 VMs.

That’s where k3sup plan came into being. My slicer tool can emit a JSON file with the hostname and IP address of its VMs. I took that file from all four servers, combined it into a single file, then ran the new command. The command generates a bash script against each of the VMs, allocating a set value to act as servers via a --servers flag. The output can then be run using the existing k3sup commands.

A new k3sup plan command for creating huge clusters

This command may make it into the k3sup repository, but I’m still iterating on it. Let me know if it’s something you’d be interested in.

Load balancing the server VMs

The 5x server VMs will load balance the API server, but are only accessible within a private network on the Equinix Metal servers, so I used a TCP load-balancer (mixctl) to expose the private IPs via the server’s public IP:

rules.yaml:

version: 0.1

- name: k3s-api

from: 147.28.187.251:6443

to:

- 192.168.1.19:6443

- 192.168.1.20:6443

- 192.168.1.21:6443

The public IP of the server was then used in the k3sup plan command via the --tls-san flag.

There was one other change that I made to k3sup, whenever you join a new node into the cluster, the command first makes an SSH connection to the server to download the “node join token”, then keeps it in memory and uses it to run an SSH command on the new node.

That overwhelmed the server when I ran all 120 k3sup join commands at once, so now k3sup node-token will get the token, either into a file or into memory, and can then be passed in via k3sup join --node-token.

What did we change in OpenFaaS?

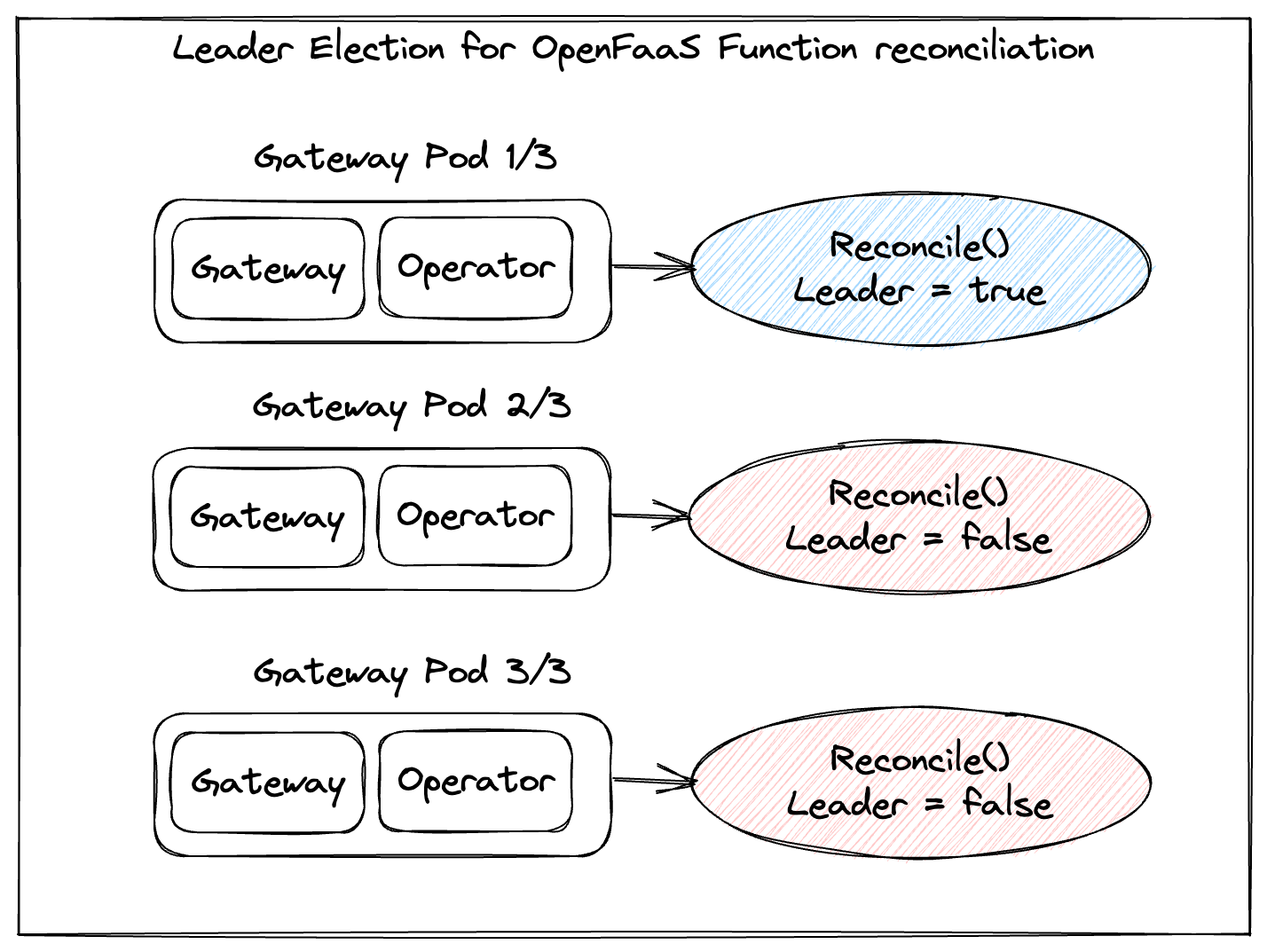

Leader election

I was in two minds to implement lease-based Leader Election, because it’s a divisive topic. Some people haven’t had any issues, but others have had significant downtime and have experienced extra load on the API server due using it.

Lease-based leader election

When three replicas of the Gateway Pod start up, each starts a REST API which can serve invocations, and the REST API for configuring Functions. However, only one of the three replicas should be performing reconciliation of Functions into Deployments and Services, so whichever takes the lease will act as a leader, and the others will just stand by. If the leader gives up the lease due to a graceful shutdown, another will take over. If the leader crashes or a spot instance is terminated, then the lease will expire after 60s and another replica will take over.

Leader Election is optional and disabled by default, but if you are running more than one replica of the gateway, it’s recommended, and prevents noise from conflicting writes or updates, which must in turn be evaluated by the Kubernetes API server and OpenFaaS.

operator:

# For when you are running more than one replica of the gateway

leaderElection:

enabled: true

See also: client-go leader-election sample

QPS and Burst values available in the chart

We’ve made the QPS and Burst values for accessing the Kubernetes API, and for the internal work-queue configurable by Helm, so people with very large clusters or very small ones can tune these values accordingly. We’ve also upped the defaults to sensible numbers.

operator:

# For accessing the Kubernetes API

kubeClientQPS: 100

kubeClientBurst: 250

# For tuning the work-queue for Function events

reconcileQPS: 100

reconcileBurst: 250

Endpoints are replaced with EndpointSlices

EndpointSlices were introduced into Kubernetes to reduce the load generated by service meshes and IngressControllers. Instead of querying a single item, a set of items can be returned for endpoints for a given service.

We’ve switched over. You’ll see a benefit if you run lots of replicas of a function, but it won’t have much effect when there are a large amount of functions with only one replica.

Here’s how you can compare how the two structures look:

# Deploy a function

$ faas-cli store deploy nodeinfo

# Scale it to 5/5 replicas

$ kubectl scale deploy/nodeinfo openfaas-fn --replicas=5

# View the endpoints

$ kubectl get endpoints/nodeinfo -n openfaas-fn -o yaml

# View the slices, you should see one:

$ kubectl get endpointslice -n openfaas-fn | grep nodeinfo

nodeinfo-9ngtv IPv4 8080 10.244.0.165 8s

# Then view the structure of the slice to understand the differences

$ kubectl get endpointslice/nodeinfo-9ngtv -n openfaas-fn -o yaml

In this case, there were 5x endpoints that would have to be fetched from the API, but only one EndpointSlice, making it more efficient to keep in sync as functions scale up and down.

API reads are now cached

There were 2-3 other places where direct API calls were being made during the reconciliation loop or in the HTTP API. For read operations, using a cached informer is more efficient. So we’ve done that and it means already reconciled functions pass through the sync handler in 0ms.

You’ll see a new log message upon start-up such as:

Waiting for caches to sync for faas-netes:EndpointSlices

Waiting for caches to sync for faas-netes:Service

Once the initial cache is filled, a Kubernetes watch picks up any changes and keeps the cache up to date.

Many log messages have been removed

We took the verbosity down a notch or two.

With previous versions, if a Function CR had been created, but not yet reconciled, then the logs for the operator would have printed a message saying the Deployment was not available, whenever a component tried to list functions. That was noise that we just didn’t need so it was taken away.

The same is the case for when a function is deployed via REST API, we used to print out a message saying “Deploying function X”. Well, that’s very noisy when you are trying to create 15000 functions in a short period of time.

Lastly, whenever a function was invoked, we printed out the duration of the execution. We removed the noise, because printing a log statement for each invocation only increases the noise for log aggregators like Loki or Elasticsearch. Imagine how many useless log lines you would have seen from a load test over 5 minutes with 100 concurrent callers?

Show me the Functions

After having got to 6500 functions without any issues on my own hardware at home, I decided to go large for the weekly Community Call where we deployed 15k functions across 3 different namespaces, with 5000 in each.

The video recording includes a short 4 minute introduction to explain what viewers are going to see, who may not have already read this blog post.

See also: Multiple namespaces

What’s next?

Not only have we fixed the customer issue where the operator seemed to “lock-up” at 3500, functions, but with the knowledge gained by writing actuated, we were able to test 15000 functions in a cost efficient manner using bare-metal hosts on Equinix Metal.

The updated operator has already been released for OpenFaaS Standard and OpenFaaS for Enterprise customers. You don’t have to be running at massive scale to update and get these enhancements.

Kevin, mentioned earlier runs OpenFaaS with much fewer functions, but with a heavier load.

When he saw the video on the community call he remarked:

“The amount of work that has gone into OpenFaaS over the years to support customers is incredible. Good job, really well done.”

Just upgrade your Helm chart to get the latest changes, and if you’d like to use leader election, see the notes earlier in this post or in the values.yaml file under the operator section.

You may also like:

- Build a Multi-Tenant Functions Platform with OpenFaaS

- How and why you should upgrade to the Function Custom Resource Definition (CRD)

- Meet the next-gen dashboard we built for OpenFaaS in production

Do you also need to test at scale - efficiently?

How are you testing your Kubernetes software at massive scale? Do you just run up a 2-3k USD / mo bill and hope that your boss won’t mind? Maybe you are the boss, wouldn’t it be nice to have a long term large test environment always on hand?

If you think you’d benefit from the “slicer” tool I built as part of this support case, please feel free to reach out to me directly.

Here’s a separate video explaining how the slicer works with k3sup plan.

Example slicer config for 3x servers and 10x workers on a machine with 128GB of RAM and 64 threads.

config:

# Total RAM = 128GB

# Total threads/vCPU = 32

host_groups:

- name: servers

count: 3

vcpu: 4

ram_gb: 8

# RAM = 24, vCPU = 12

- name: workers

count: 10

vcpu: 2

ram_gb: 8

# RAM = 80, vCPU = 20

Disclosure: Ampere Computing provided me with the Ampere Developer Platform at no cost, for evaluation and for open source enablement. Ampere Computing is a customer of our secure CI/CD platform actuated.dev.