Alex takes a look at the architecture of OpenFaaS and why you can say goodbye to coldstarts.

I started out with OpenFaaS in 2016 when I was frustrated with the developer experience and portability of cloud functions.

I knew that containers were going to be important for portability, but can you blame me for thinking that I would be able to run one container per HTTP request? That turned out to be a non-starter, but as a community we came up with something that’s used broadly in production today.

In this article, I’ll cover the reason why containers are slow to start - particularly on Kubernetes, then take you through our research and development that ultimately led to not needing cold-starts, or not needing to see them in OpenFaaS. There’ll be plenty of links and resources if you want to go deeper, and a FAQ towards the end.

What is the lifecycle of a container?

Let’s look at the lifecycle of a container, or as I like to call it “Why is this thing so slow?”

There’s several things that happen when a container is scheduled on Kubernetes:

- The container image has to be fetched from a remote registry

- The container has to be scheduled on a node with available resources

- The container has to be started and have its endpoint registered for health checks

- A health check has to pass for the container’s endpoint

And when all that’s complete, you can probably serve a request.

Around the same time Phil Estes of (then at IBM) was writing a container benchmarking tool called Bucketbench. This was a problem that other people were clearly interested in solving. Phil’s tests showed that for pre-pulled images, runc (the lowest level of a container in Kubernetes) could start a container in a fraction of a second.

So I tried it out, and found that this process would take several seconds, even for small container images, or images that were already cached on my cluster.

Why was that? Primarily because the health checks in Kubernetes at a minimum of every 1 second, so if you miss the first, you have to wait for the second to pass. Thus you get your 2 second latency for a cold-start.

Start processes, not containers

So after some experimentation I decided that the container should be created at deployment time, and perhaps we should use process-level isolation instead.

Process-level isolation meant running one process per request as per the good old CGI days of the early internet.

In order to have a persistent container that could serve more than one request using process-level isolation, I needed a kind of init process, something that could watch over the container and launch these processes as required.

A process needed a standard way to communicate and I picked up on the idea of UNIX pipes as a way to make this happen in every programming language and every kind of binary I was familiar with. We then needed a way to marshal from our users to the processes, and back again and I used HTTP for that.

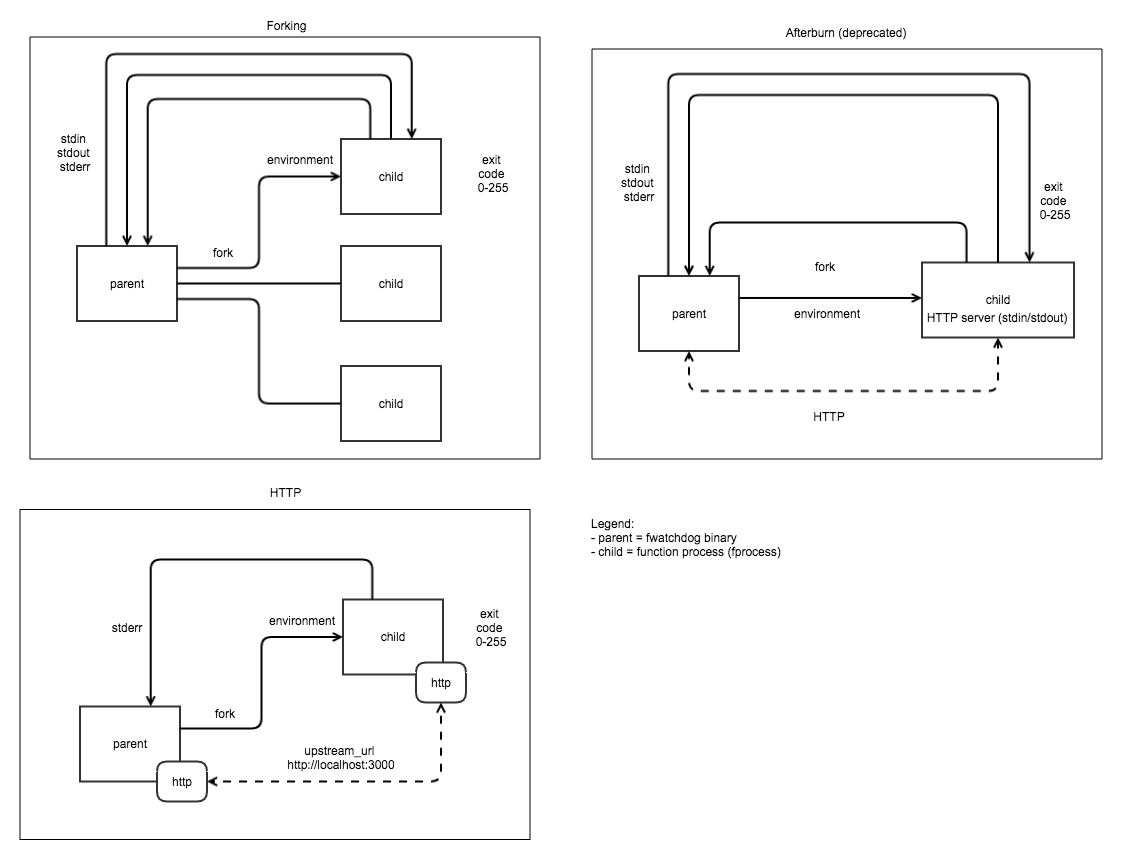

I called this program “the watchdog”:

The OpenFaaS watchdog creates a process per request

The HTTP request body is marshalled into the process via STDIN, with the HTTP headers, Path and Method being turned into environment headers prefixed with X-Http-. Then the response for the HTTP response is read from STDOUT. STDERR can either redirect to the container logs, or be combined into the function’s output.

Creating a process on a modern machine was many times faster than creating and scheduling a container on Kubernetes, we’re talking of < 100ms per request. Now that may still sound like a large number to you, but remember that it’s a lot better than multiple seconds!

In fact I can recall a company reaching out to me that was using OpenFaaS and Node.js in production. A Node.js process is notoriously slow to start up, if you don’t believe me, try running it on a Raspberry Pi and you’ll see what I’m talking to. Then compare that to Python or Go.

So we started to see an imbalance: Go and Python started instantaneously, but Node.js and Java took 5-10x times longer to start per request.

Start time by language

You may be surprised to hear that that the Classic watchdog is still used in production today, and many users do not care about this latency because of the value they get and the type of workloads they run.

How can we re-use the same process for multiple requests?

I started to ask myself: “How can we re-use the same process for multiple requests?” Learning from the past, CGI had also faced this problem and came up with “Fast CGI” a solution that multiplexed multiple requests into a single binary process for greater efficiency.

My version of this was called Afterburn and I shared a blog post with Java and the JVM - the increase in performance was marked.

The increase in performance was marked

But Afterburn relied on me writing a stream multiplexer in each language that we needed to support: openfaas-incubator/nodejs-afterburn and openfaas-incubator/java-afterburn.

I decided that we needed a standard way to re-use the same process instead - one where I didn’t need to maintain bespoke code for every supported language. That turned out to be HTTP.

The of-watchdog was born and added HTTP-level multiplexing for requests:

New watchdog modes

The new of-watchdog brings latency per request down to 1ms or less and can handle high load.

You’ll find it used in the most modern Go, Python, Java and Node.js templates that we maintain.

The other side-effect of moving of adding better support for HTTP was that you could now run regular microservices on OpenFaaS and have them scaled and monitored in the same way as your functions.

Here are a number of examples showing the use-case with concrete examples:

- Introducing stateless microservices for OpenFaaS

- Build a Flask microservice with OpenFaaS

- Serverless Node.js that you can run anywhere

- Get started with Java 11 and Vert.x on Kubernetes with OpenFaaS

So dude, where are my coldstarts?

Cold starts occur at two times during your function’s lifecycle:

1) Initial deployment The function is deployed for the first time, and must go through the lifecycle we outlined in the introduction. This can be slow because it involves pulling an image from a remote registry, unpacking it, and having it pass a health check.

2) During horizontal scaling Each time you scale from N to N+1 replicas of a function, the same process takes place, but may be hidden because we have at least some replicas to take the current load of the system.

Here’s our solution for the cold-start problem: don’t have one.

What do I mean?

Think about it. Where do you see coldstarts? On massive SaaS-style cloud provider products like AWS Lambda, where hundreds of thousands of functions lay idle - potentially for days at a time.

You are not Google or Amazon Web Services, so you do not have the same constraints as they do. You don’t need to run 200,000 mostly idle functions for thousands of different customers and bill them per second for their compute time.

Now don’t get me wrong, cloud functions can be incredibly convenient and are a good choice for many people. OpenFaaS is built for those who value simplicity and need portability, greater flexibility and an intuitive developer experience.

OpenFaaS from day 1 ran a minimum of 1 replica of every function, always. You could set this minimum number higher if you wished, but it was at least 1. Scaling to zero wasn’t something that users talked to us about for quite some time, so we didn’t prioritise it.

In 2018 one of our customers was running up a large bill on Google Cloud, and asked if we could introduce automated scale to zero. We did that, but made it optional, so you could have tight control over which functions were going to incur a coldstart.

So what did you do about coldstarts then?

- We then tuned the OpenFaaS helm chart so that if you needed fast scale up if you needed, by reducing the health check for functions to as low as 1 second.

- We also experimented with letting the function receive traffic before it was marked as healthy by Kubernetes. This was interesting, but mostly resulted in HTTP errors. Health checks exist for a reason.

- We made scale to zero opt-in per function, not a global setting

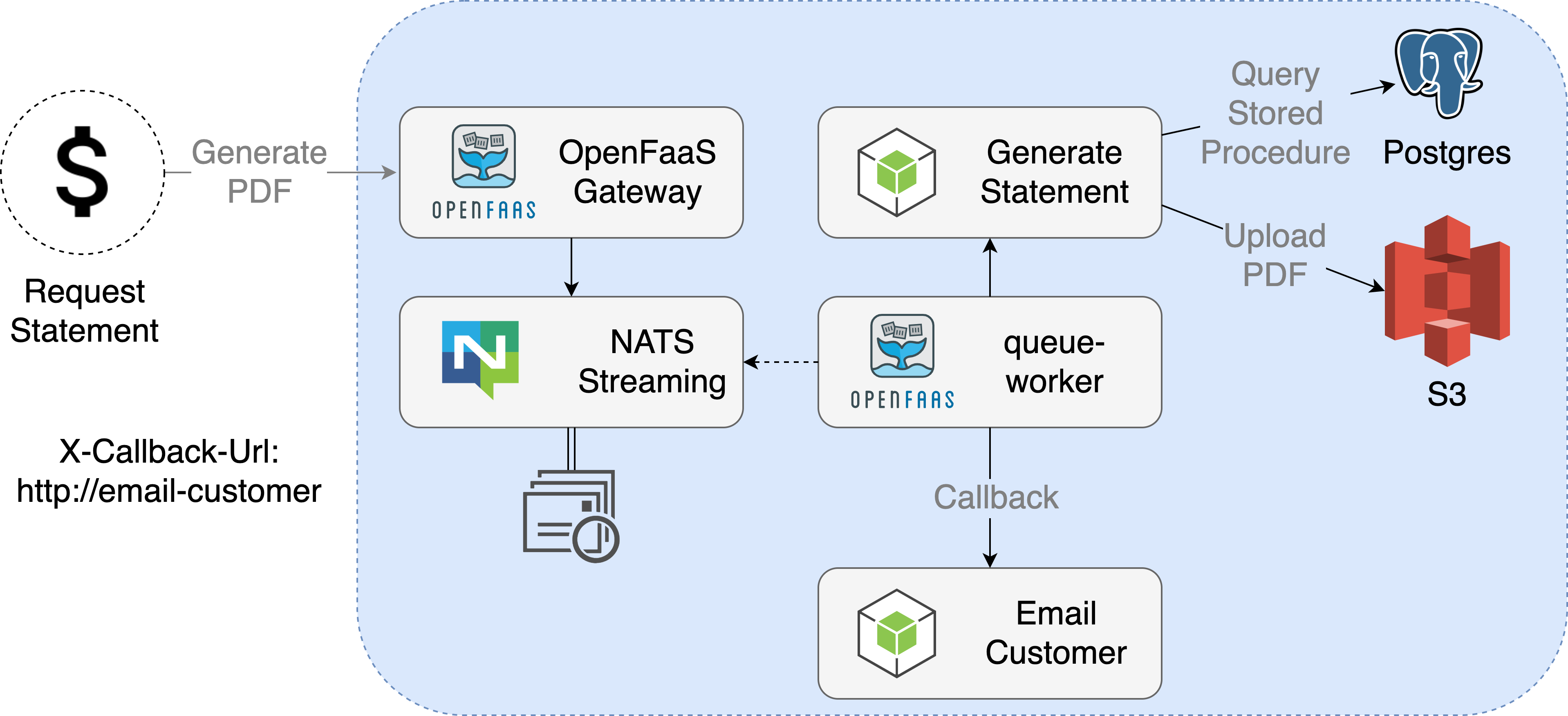

- Async invocations including an optional callback URL

Now, if your function is not user-facing and can run in the background, you can make your cold-start disappear in another way, by running it asynchronously.

FAQ

- So why don’t you deprecate the Classic Watchdog?

The Classic Watchdog is ideal for running code in languages which have no support for a HTTP stack such as bash, Powershell and COBOL. Any binary, even the AWS CLI can be made into a function through the classic watchdog. You can think of it like a converter from a CLI to a HTTP REST API. See also: Turn Any CLI into a Function with OpenFaaS - Alex Ellis’ Blog

-

Why do I need watchdog anyway?

Both of the watchdogs add: a standard, known interface that the gateway relies upon for metrics, health checks, graceful shutdowns and logging.

Whilst we don’t recommend it, if you’re using a HTTP microservice that conforms to the Workloads spec, then technically you may be able to get away without using it.

Since the OpenFaaS watchdogs use HTTP on port 8080, they can technically be run on SaaS products like Google Cloud Run, Heroku and DigitalOcean AppPlatform - and visa versa.

-

Why didn’t you use plugins?

This is a route taken by other frameworks like Nucio, but support for plugins varies between languages and introduces similar issues to afterburn. I.e. needing bespoke code for each language.

-

Why don’t you maintain a pool of workers and inject their source code?

This is a technique popularised by a couple of other frameworks in the space such as OpenWhisk and Fission. Containers are designed to be immutable for a predictable lifecycle and for tight control over what actually exists and runs in the cluster. We recommend using a read-only filesystem with OpenFaaS for maximum security. Injecting source code may give the impression of a faster cold-start, but we think there are better ways to achieve this goal without those tradeoffs.

-

“It’s not a function unless it’s completely immutable!”

According to what definition? If you check out our ADOPTERS.md file, you’ll see various sizes of companies that use OpenFaaS in production and find value from its developer experience and portability between clouds. Even AWS Lambda is not completely immutable, it may be limited to run one request per container, but those containers may be reused multiple times.

OpenFaaS functions allow you to set up a database connection, or to load a large machine learning model and have that cached between requests. This combined with a read-only filesystem means you can keep your code immutable.

-

“But what if I really need to limit concurrency for each function?”

Imagine that you’re running ffmpeg within a container as part of job to convert full-length videos into previews reels. You’d need to limit the amount of requests per container so that you don’t run out of storage for the input or output file, and RAM could also be important, you wouldn’t want to overload a container and get an OOM error.

The

max_inflightenvironment-variable configures the watchdog to limit the number of concurrent requests per container. These can then be retried with an exponential backoff, and the “busy messages” are used by some of our customers to scale up the function.

Summing up

It’s now 5 years since we started OpenFaaS. The journey so far has involved lots of research & development, feedback from customer and community and iteration.

OpenFaaS - an independent effort, focusing on developer experience, operational simplicity and community

In 2022, our of-watchdog gives us a standard interface for making containers more efficient for handling functions. It can serve requests in a round-trip in less than 1ms and handle high concurrency within each container (replica) in your cluster. The cold-start is optional, and where you opt-in to have one, we have ways to mitigate its impact and “hide it” from your users.

Scaling your functions down to a minimum replica count or to zero replicas when not in use, can save you money over time - by reducing the total amount of nodes you need in your cluster. There are a few other tricks we’d be happy to share with you about running OpenFaaS in Production and saving on cloud costs.

In the future, as Kubernetes becomes more adept at starting containers quickly, OpenFaaS will be able to leverage that work too.

If you’d like to learn more about the project and community, check out:

- My OpenFaaS Highlights from 2021

- Serverless For Everyone Else (OpenFaaS handbook)

- Check out OpenFaaS Pro - OpenFaaS for production

- Fork/star the of-watchdog on GitHub

Or reach out to talk to us on Twitter or via email.